An essential consideration in managing portfolios in this way is asset location—the selection of the entity, owner, or account type in which an asset is held.

As portfolio managers for wealthy families and individuals, we are frequently called upon to rebalance portfolios because of changing client circumstances, to invest or distribute cash, or to anticipate or react to market movements. The rebalancing process occurs not only at the individual strategy level but also across a client’s broader asset allocation. Rebalancing ensures harmony between asset classes and investment strategies and is a fundamental aspect of holistic portfolio management.

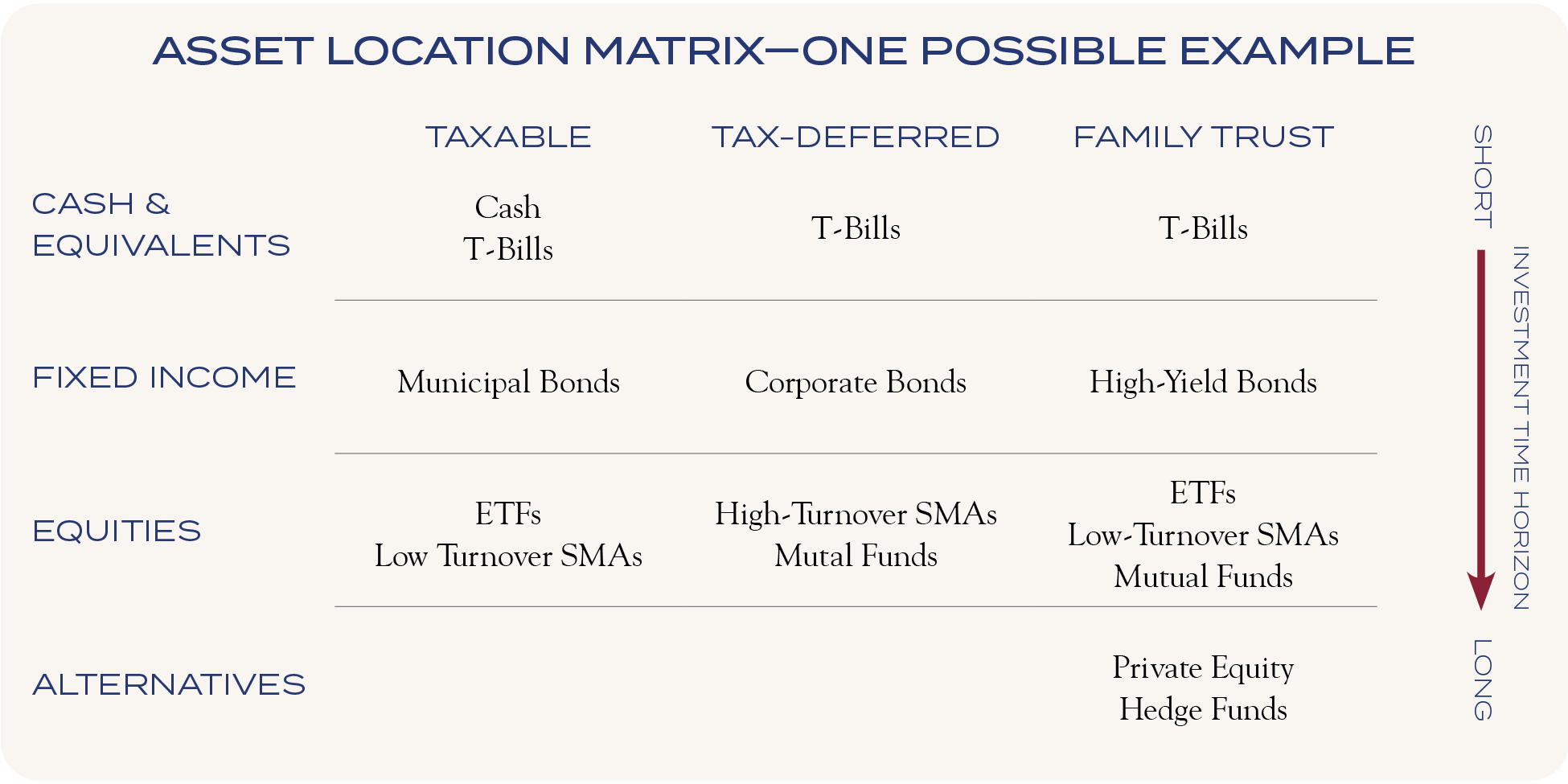

An essential consideration in managing portfolios in this way is asset location—the selection of the entity, owner, or account type in which an asset is held. While each client’s goals are unique, three factors consistently guide effective asset location decisions: tax efficiency, liquidity requirements, and the investment time horizon.

Tax Efficiency

Tax considerations often guide asset location decisions. These decisions can reduce capital gain exposure, defer tax liabilities, and enhance compounding over time. A well-known example is the use of municipal bonds in taxable portfolios and corporate bonds in tax-deferred accounts. While both investments are in fixed-income instruments, proper placement allows managers to maximize the tax-exempt benefits of municipal bonds and take advantage of higher corporate yields without an immediate tax liability.

Proper placement allows managers to maximize the tax-exempt benefits of municipal bonds and take advantage of higher corporate yields without an immediate tax liability.

Another common strategy is the use of IRAs for “tax-free” rebalancing—executing portfolio adjustments within a tax-deferred account to avoid triggering capital gains. This approach can be effective when rebalancing within a single asset class, such as equities. For example, shifting exposure between large- and small-cap stocks or rotating between growth and value strategies can be done without tax consequences.

However, when rebalancing involves shifts between asset classes—such as reducing equity exposure in favor of fixed income—managers must be mindful of how this impacts the broader asset allocation, particularly the distribution of cash and bonds between portfolios.

Buy-and-hold, low-turnover strategies—such as certain Separately Managed Accounts (SMAs) and Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs)—are well-suited for taxable accounts. Low-turnover SMAs typically generate fewer realized capital gains due to minimal trading activity, while ETFs benefit from an inherent tax efficiency over mutual funds, which must distribute gains. This makes ETFs a very tax-efficient choice in taxable portfolios.

Conversely, high-turnover SMAs and mutual funds are generally better suited for tax-deferred accounts such as IRAs and qualified retirement plans. Managers can trade more frequently and opportunistically in tax-deferred environments without incurring the immediate tax consequences of capital gains. Taxes typically come from the overall appreciation of the portfolio, unrelated to trading, dividends, and income. Even then, taxes are often deferred until withdrawal, usually in the form of ordinary income tax and sometimes not at all.

Mutual funds, in particular, are required by law to distribute at least 90% of realized capital gains annually. As a result, investors may receive gains distributions regardless of when they purchased the fund or their individual gain/loss position, potentially leading to an unexpected tax burden. Whenever possible, it is more advantageous to hold mutual funds in tax-deferred accounts where these distributions do not create immediate tax liabilities.

Liquidity

Effective asset location must consider liquidity needs as they relate to each individual investor or entity and not across all portfolios combined. While a client might be risk-averse and may prefer a balance of investments that favors high cash positions and fixed income, it is important to balance that allocation across various account types such that different types of liquidity needs are met. Examples of liquidity needs might include annual spending requirements and unforeseen expenses, mandatory trust payments to trustees or beneficiaries, and IRA required minimum distributions (RMDs). In cases such as a client’s annual spending, cash is completely removed from the asset base. For RMDs and trust distributions, cash may simply move from one portfolio to another and remain part of a client’s overall investable assets. It is important to understand the difference when structuring portfolios.

For example, as with the “tax-free” rebalancing mentioned earlier, equity exposure might be reduced within tax-deferred portfolios. There are good reasons for such rebalancing. Many times, cash and bond allocations are built up in an IRA as an “anchor to windward” against volatile equity markets. This helps from an investment perspective, but has no impact on a client’s liquidity beyond the required distributions, as taxes limit the accessibility of that cash. This can have a major impact on liquidity if planning does not account for reserves outside tax-deferred portfolios.

Similar issues can arise with trusts depending on various factors affecting each entity. Clients and advisors should make sure to understand the purpose for which each entity was created as well as the particulars of each trust. In doing so, managers will be prepared for any mandatory distributions and can balance payments against potential appreciation.

For example, income trusts, annuity trusts, and unitrusts all distribute in different ways (income, fixed dollar distributions, and percentage distributions), and investments should be structured accordingly to achieve a client’s desired outcome. In cases when the trust and the beneficiary’s assets are managed in accordance with each other, the transfer of cash (or other securities) from a trust to its beneficiary is similar to an IRA distribution in that liquidity is constrained by trust parameters, like RMDs, which are limited by tax constraints. As such, the overall asset base will stay the same after a distribution, and there may be no change in liquidity beyond the distribution.

Each entity has specific liquidity needs relating to its own distributions, which should inform levels of overall sources of liquidity and a client’s ultimate access to spendable cash.

In both examples, each entity has specific liquidity needs relating to its own distributions, which should inform levels of overall sources of liquidity and a client’s ultimate access to spendable cash.

To avoid potential hang ups, managers should strategically build up cash reserves in taxable portfolios over time, so funds are readily available when needed without causing unintended tax consequences or investment misalignments.

Investment Time Horizon

Many portfolio managers work with multi-generational families, investing across a variety of account types, ownership structures, and entities to optimize returns for the group as a whole. As discussed, certain investments are better suited for specific entities due to their structural characteristics. However, investment style and strategy are also critical in determining asset placement.

A widely accepted principle is that riskier, more volatile investments are best suited for long-term vehicles such as legacy trusts and certain tax-deferred portfolios. The extended time horizon of these accounts helps mitigate the short-term impact of volatility, providing time for investments to recover from downturns.

This approach is generally prudent, as it allows taxable portfolios to be structured with liquidity in mind, ensuring that cash flow needs are met while allowing other accounts to remain focused on long-term growth. However, careful attention must be paid to avoid overburdening any single entity with a concentrated investment strategy. The entire structure could suffer during market downturns if all investments within a given entity are highly correlated or exposed to similar risks.

The goal is to balance long-term growth potential while guarding against extended periods of downside volatility that could erode an entity’s future value.

A key tenet of diversification is recognizing that not all investments will be top performers at the same time. Market cycles naturally favor different strategies at different periods. As a result, it is wise to diversify not only across an overall portfolio but also within individual entities as well. The goal is to balance long-term growth potential while guarding against extended periods of downside volatility that could erode an entity’s future value.

For example, within an asset allocation across portfolios, an entity with a long life, such as a family trust, might skew slightly towards investments farther out on the risk/return scale. Investing in this way takes advantage of a long time horizon to absorb any periods of underperformance for the higher-risk strategies. However, managers should not overcommit and exclude core strategies altogether. Keeping a base of core investments in a longer-term entity would dampen periods of underperformance for the higher-risk strategies. The effect is a steadier pattern of returns and less volatility in a portfolio that is geared to benefit over time from investments that may take years to mature.

Portfolio construction and asset allocation involve many considerations. Beyond investment strategies and market conditions, family dynamics and personal experiences often significantly shape a client’s portfolio decisions. A successful investment approach requires not only market expertise but also a deep understanding of each client’s unique priorities and financial goals.

The key to effective asset allocation and investment placement across entities is open dialogue and clear communication between managers and clients. Thoughtful discussions about the factors that matter most, along with an awareness of how each decision impacts long-term objectives, can lead to more informed and effective portfolio decisions.

This communication contains the personal opinions, as of the date set forth herein, about the securities, investments and/or economic subjects discussed by Mr. Sim. No part of Mr. Sim’s compensation was, is or will be related to any specific views contained in these materials. This communication is intended for information purposes only and does not recommend or solicit the purchase or sale of specific securities or investment services. Readers should not infer or assume that any securities, sectors or markets described were or will be profitable or are appropriate to meet the objectives, situation or needs of a particular individual or family, as the implementation of any financial strategy should only be made after consultation with your attorney, tax advisor and investment advisor. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. © Silvercrest Asset Management Group LLC