Defining Intergenerational Equity

“Prudence is the virtue by which we discern what is proper to do under various circumstances in time and space.”

—John Milton

Trustees of endowed institutions face a range of variables unknown to nonprofit directors in recent decades. As stewards of institutions with timeless missions and perpetual capital, their charge is to navigate today’s challenges and opportunities while anticipating future needs stretching well beyond their limited board tenures.

The often-quoted admonition, “Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof,” encourages a focus on the present, suggesting as it does that future problems will work themselves out. When it comes to endowment investing, however, such an approach falls short of the regulatory requirements outlined in the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act (UPMIFA). The Act governs the standard of conduct of charitable organizations and the duties of their volunteer directors.

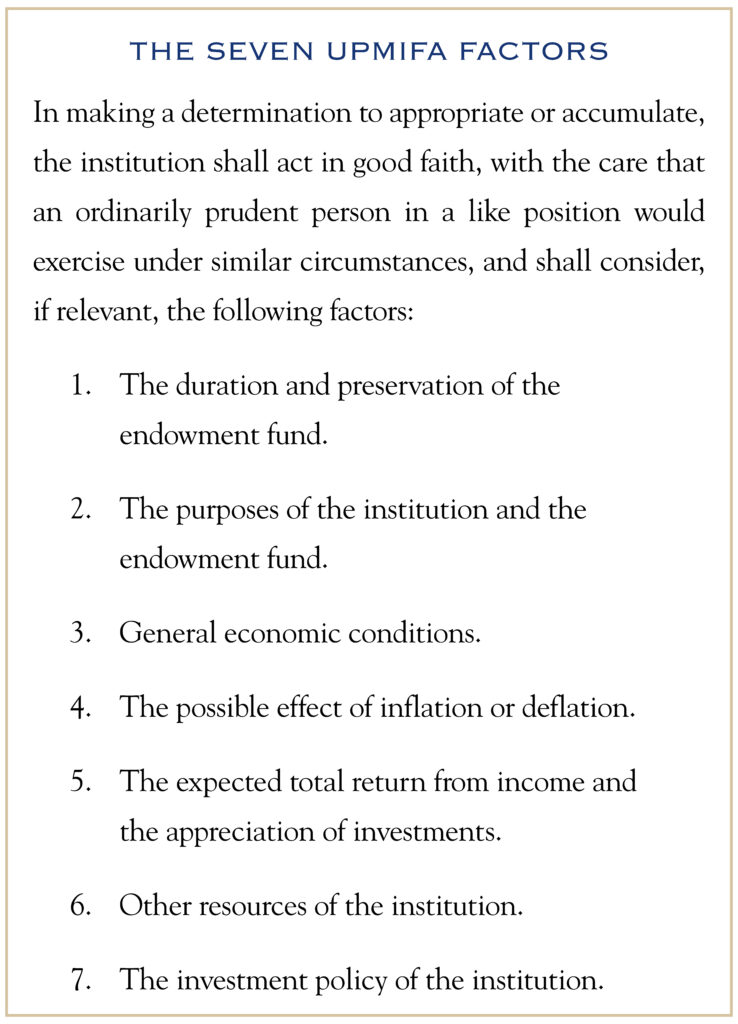

UPMIFA provides seven rules for weighing the appropriateness of decisions relating to the “Expenditure or Accumulation of Endowment Funds”—in other words, how much a board should spend now on programming versus saving and investing for the future.

The Act instructs trustees of endowed charities to consider long-term factors such as time horizon (which may be in perpetuity) and the strategic mission of the organization along with near-term issues including the state of the economy and markets, inflation (or deflation), the nonprofit’s other sources of income, the expected total return of the portfolio, and the investment objectives and guidelines articulated in the organization’s Investment Policy Statement.

Intergenerational Equity

Nonprofit boards must struggle with the push and pull of the present versus the future in seeking to balance what is often referred to as “intergenerational equity.” Endowment asset allocations and risk/return objectives must be designed to provide for current support while safeguarding principal for future needs. Trustees are guilty of imprudence under UPMIFA if current spending exceeds 7% of principal or if endowment assets are not effectively diversified to deliver both growth and income over market cycles.

The objective is to ensure that current and future generations receive the same level of charitable benefits. Excessive current spending or poor diversification leading to significant investment loss can permanently impair an endowment’s ability to fund future needs.

The challenge is especially acute for today’s directors, who are forced to consider inflation levels unseen in more than three decades, along with market conditions clouded by falling economic growth rates, a weakened banking sector, and mounting geopolitical tensions.

The Impact of Inflation

To help ensure equity between generations, trustees must ensure that current spending does not exceed the endowment’s purchasing power, which can be defined as its nominal return minus inflation. For years, endowment investment policies routinely targeted a 7% nominal return, which allowed for an annual spending rate of 5% plus 2% for inflation.

Suppose inflation is 3%, 4%, or higher over a multi-year period. Either endowment spending policies must decrease to less than 5%, or their investment policies must become more aggressive (i.e., riskier) by targeting a greater than 7% nominal return. The former option arguably harms current beneficiaries while the latter poses a potential negative impact on future beneficiaries, not to mention possibly impairing the long-term viability of the charity.

CPI is a Poor Gauge of Institutional Inflation

Inflation impacts every charity in a distinctive way. While the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is a useful measure of inflation for U.S. households, it may align poorly with a nonprofit’s actual expenses. A household’s largest typical expense is housing at more than 40% of income. In comparison, an endowed nonprofit’s largest expense is often employee salaries and benefits which frequently exceed 50% of

annual budgeted costs.

Post-COVID inflation has raised labor costs associated with hiring and retaining professionals, leading to significant construction and other related cost overruns for nonprofits. Investment and finance committees need to understand the impact of actual rising costs on their budgets rather than focusing on headline inflation as characterized by CPI.

Crimped Growth at Home & Abroad

The war in Ukraine, the potentiality of changes to bank lending practices, manufacturing’s return to onshoring, and other factors are impacting general economic conditions, with most economists agreeing that global and U.S. economic growth will slow. Such a slowdown will negatively affect revenues, earnings, and valuations of businesses worldwide.

Asset allocations that have worked since the Global Financial Crisis and their attendant risk/return assumptions may no longer deliver the anticipated annual 5% real return with the acceptable level of risk on which many nonprofit committees have come to depend.

What, then, are committee members to do?

Juggling Dual Obligations to Both Current & Future Generations

Uncertainty regarding future price stability and economic growth is a given, as is the impact on stock prices, credit risk, and the valuation of other investable assets. While unknowns persist, trustees must nevertheless use their best judgment in setting spending rates and asset allocations with reasonable risk/return expectations that can meet the needs of both current and future stakeholders.

Three Keys to Success: Liquidity, Long-Term Growth, & Leveraging Budget & Balance Sheet

Liquidity

An inverse relationship should exist between illiquidity and uncertainty. A well-capitalized Ivy League university endowment can likely take on significant portfolio illiquidity because its near-term risks are relatively limited. Even a string of back-to-back Black Swan events would be unlikely to jeopardize its existence ten years out, given its endowment size, access to the bond market, tuition pricing power, balance sheet, and reputation. On the other hand, a small liberal arts college in a remote location with declining admissions and rising costs potentially needs much greater liquidity.

Every nonprofit has a distinctive mission, a financial profile, and specific cash-flow considerations. With their investment advisor’s assistance, investment committees must tailor the asset allocation and investments to the organization’s unique circumstances. One way to gauge appropriate liquidity is to ask how many years’ worth of endowment spending should be available in a worst-case scenario.

If there are relatively few variables and non-endowment available cash on hand, then perhaps one year of spend in cash or cash-like investments provides an appropriate buffer. However, if budgetary variables exist and near-term programming is uncertain, as was the case, for example, with many already struggling smaller museums and performing arts institutions hit hard by the Global Pandemic lockdowns, then having two, three, or even more years of annual spending on hand could be prudent.

Long-term Growth

In recent years there has been a correlation between liquidity and returns. Liquid fixed income provided paltry returns, while illiquid venture capital and private equity drove endowment returns. Putting aside the question of whether that correlation continues into the future, endowment investors must face the reality of devising a portfolio capable of achieving annualized returns in excess of their spending rates.

The only way to maintain current spending rates without decreasing the purchasing power of the endowed assets over time is to construct a portfolio that can achieve, in most cases, a 5% or higher annualized real rate of return. Even with interest rates on the rise, typical current fixed income strategies deliver returns well below that, which leaves public and private equity as the primary drivers

of portfolio growth.

While the old rule of thumb was to have a 60% allocation to equities and 40% to fixed income, today, it is not uncommon for endowments to have 70%, 80%, or more allocated directly to equities and to alternative investments whose returns are closely correlated to equities. Under such circumstances, investment committees need to rely on an investment advisor to walk them through portfolio risk at the asset class level, which resides with each underlying manager and strategy, and the possible risk correlations between managers. Trustees lacking access to this level, location, and correlation of portfolio risk are largely incapable of exercising their obligations under UPMIFA.

Leveraging Budget & Balance Sheet

Given increased economic and market uncertainty, today, more than ever, members of investment committees and their investment advisors must focus not simply on investments and the markets but on the finances of the organizations they serve. Strategic portfolio decisions relating to spending rate, asset allocation, and liquidity must be closely aligned with organizational realities to ensure that the portfolio is designed to succeed in its dual intergenerational mandate.

The annual draw from endowed funds is only one revenue source comprising a nonprofit’s income. Investment committees must understand the variability of other revenue sources, including tuition or program services, annual giving, planned/estate gifts, government/private contracts, annuity and trust income, interest, etc. Similarly, variability is naturally embedded in expenses, from labor and program expenses to fundraising and occupancy overhead.

Only when trustees fully understand the programmatic and budgetary realities of the institutions they serve can they fully execute their duties under UPMIFA and to current and future beneficiaries of the endowed funds they steward.

This communication contains the personal opinions, as of the date set forth herein, about the securities, investments and/or economic subjects discussed by Mr. Long. No part of Mr. Long’s compensation was, is or will be related to any specific views contained in these materials. This communication is intended for information purposes only and does not recommend or solicit the purchase or sale of specific securities or investment services. Readers should not infer or assume that any securities, sectors or markets described were or will be profitable or are appropriate to meet the objectives, situation or needs of a particular individual or family, as the implementation of any financial strategy should only be made after consultation with your attorney, tax advisor and investment advisor. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. © Silvercrest Asset Management Group LLC