How is artificial intelligence affecting the labor market? By linking theory, transition, and observed outcomes, three research papers help shed light on this question. The first outlines a task-based framework to assess the susceptibility of occupations to computerization, the second helps develop a system for understanding the slow and uneven emergence of economic effects from digital and artificial intelligence, and the third provides some of the first large-scale empirical evidence on the labor market effects of generative AI. Despite widespread concern that rapid AI adoption will lead to large-scale job loss, the literature reviewed here suggests a slower, uneven process in which AI reshapes the types of jobs and tasks performed, rather than reducing employment overall.

Which Jobs Can be Automated, & Which Can’t

Progress in machine learning allows computers to perform an increasing range of nonroutine cognitive and manual tasks. As a result, occupations previously considered to have less risk from automation may now face substantial exposure to computerization.

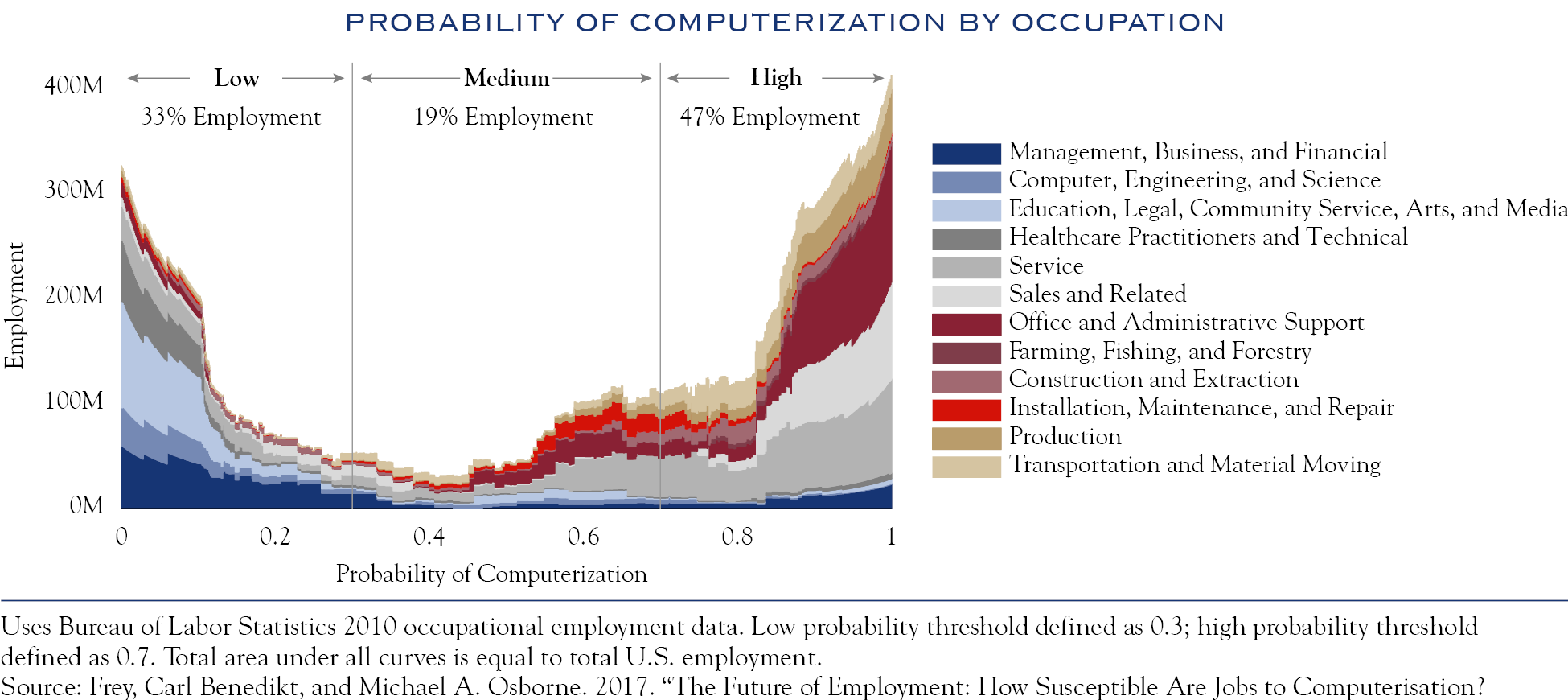

Carl Frey and Michael Osborne, in their 2017 paper,1 address the susceptibility of jobs to computerization, defining “computerization” as job automation facilitated by computer-controlled equipment. Using a novel machine learning based methodology, they estimate the probability of computerization for 702 detailed U.S. occupations and examine how these probabilities relate to occupational wage levels and educational attainment. To produce these estimates, they combined task-based labor economics with recent advances in machine learning and robotics.

Whereas earlier task content frameworks largely confined automation to routine tasks, progress in machine learning allows computers to perform an increasing range of nonroutine cognitive and manual tasks. As a result, occupations previously considered to have less risk from automation may now face substantial exposure to computerization.

At the same time, automation remains constrained by three key technological bottlenecks:

- Perception and manipulation tasks, such as those requiring fine motor skills, physical dexterity, or operation in unstructured and unpredictable environments, remain difficult for machines, despite advances in robotics and sensor technology.

- Creative intelligence tasks, which involve generating novel and valuable ideas, pose challenges because, while they can produce novelty and perform narrowly defined creative tasks, computers struggle to evaluate creative value, capture human subtlety, and adapt to shifting cultural norms.

- Social intelligence tasks, including negotiation, persuasion, and caregiving, remain resistant to automation, as machines lack robust real-time understanding of human emotions, social cues, and contextual behavior in complex interpersonal settings.

Empirically, the authors draw on data from the Occupational Information Network (O*NET). A comprehensive U.S. government database maintained by the Department of Labor, O*NET characterizes occupations in terms of skills, abilities, work activities, and work contexts, providing continuous measures that capture the importance and level of various occupational characteristics. Using these measures, Frey and Osborne identify variables that proxy for the three technological bottlenecks and manually classify a subset of occupations according to whether their tasks are automatable given current or foreseeable technological capabilities. This training set is then used to assign a continuous probability of computerization to each of the 702 occupations. To assess the potential employment impact, these probabilities are combined with Bureau of Labor Statistics employment data and weighted by occupational employment shares. The results suggest that roughly 47% of U.S. employment falls into occupations with a high probability (greater than 0.7) of computerization.

It is noted that these estimates are probabilistic rather than deterministic and could best be interpreted over the next decade or two. Computerization does not necessarily imply the elimination of an occupation; rather, jobs could be partially automated, with computers substituting for some tasks while complementing human labor in others. As a result, automation may reshape job content, raise productivity, and alter skill requirements rather than simply eliminate several jobs. The future of employment will depend not only on technological feasibility but also on how tasks are reorganized between humans and machines.

Why Productivity Can Be Mismeasured

In 2021, Erik Brynjolfsson, Daniel Rock, and Chad Syverson investigated why periods in which technology rapidly evolves are often accompanied by weak measured productivity growth.2 Early appearances of this problem, most notably Robert Solow’s observation that computers were visible everywhere except in productivity statistics (“Solow’s Paradox”), have since been seen across many previous technological transitions. Two prominent transitions discussed are electrification and the technology boom. Such productivity paradoxes are not anomalies, but rather predictable outcomes of how productivity is measured during periods of general-purpose technology (GPT) adoption.

Software and AI technologies don’t immediately generate productivity gains on their own. Rather, their economic impact depends on complementary investments, organizational restructuring and redesign, worker training, and overall firm knowledge.

Productivity slowdowns frequently coincide with the introduction of transformative technologies, precisely because these technologies require large complementary investments that are poorly captured by conventional accounting frameworks. Software and AI technologies don’t immediately generate productivity gains on their own. Rather, their economic impact depends on complementary investments, organizational restructuring and redesign, worker training, and overall firm knowledge. Investments in AI are expensive and cannot be deployed overnight, leading to a noticeable lag before the benefits are captured in national accounts. This results in periods of rapid technological diffusion, often characterized by substantial unmeasured investment activity that suppresses measured output and productivity, even as firms lay the foundations for future gains.

The argument is reinforced by introducing the concept of the Productivity J-Curve, which describes the path of productivity mismeasurement during GPT adoption. In the early phase, firms devote resources toward producing intangible capital that does not appear in measured output, resulting in an understatement of true productivity growth. As the value of these intangible assets grows, they begin to generate observable productivity. While productivity is initially understated, it may later be overstated as intangible capital stocks mature and begin generating measurable output. The creation of a J-shaped pattern provides a framework for understanding the initial slowdowns and subsequent acceleration associated with a major technological change.

Software-related intangible investment has produced a large and persistent understatement of productivity levels, suggesting that a substantial portion of productivity levels remains unobserved in official statistics.

Beyond its conceptual contribution, the authors formalize their intuition by embedding intangible capital directly into a growth accounting framework. They demonstrate that productivity mismeasurement arises from two offsetting channels: measured inputs producing unmeasured intangible outputs and unmeasured intangible inputs producing measured outputs. Standard total factor productivity measures overlook both effects, resulting in productivity being understated during periods of rapid intangible investment and overstated once intangible capital begins generating observable output. The value of intangible investments is inferred using firm market valuations, considering that financial markets capitalize the expected returns to both measured and unmeasured assets. Utilizing this approach, they find that while research- and development-related intangibles currently generate little net mismeasurement, software-related intangible investment has produced a large and persistent understatement of productivity levels, suggesting that a substantial portion of productivity levels remains unobserved in official statistics.

Six Early Signals From The Labor Market

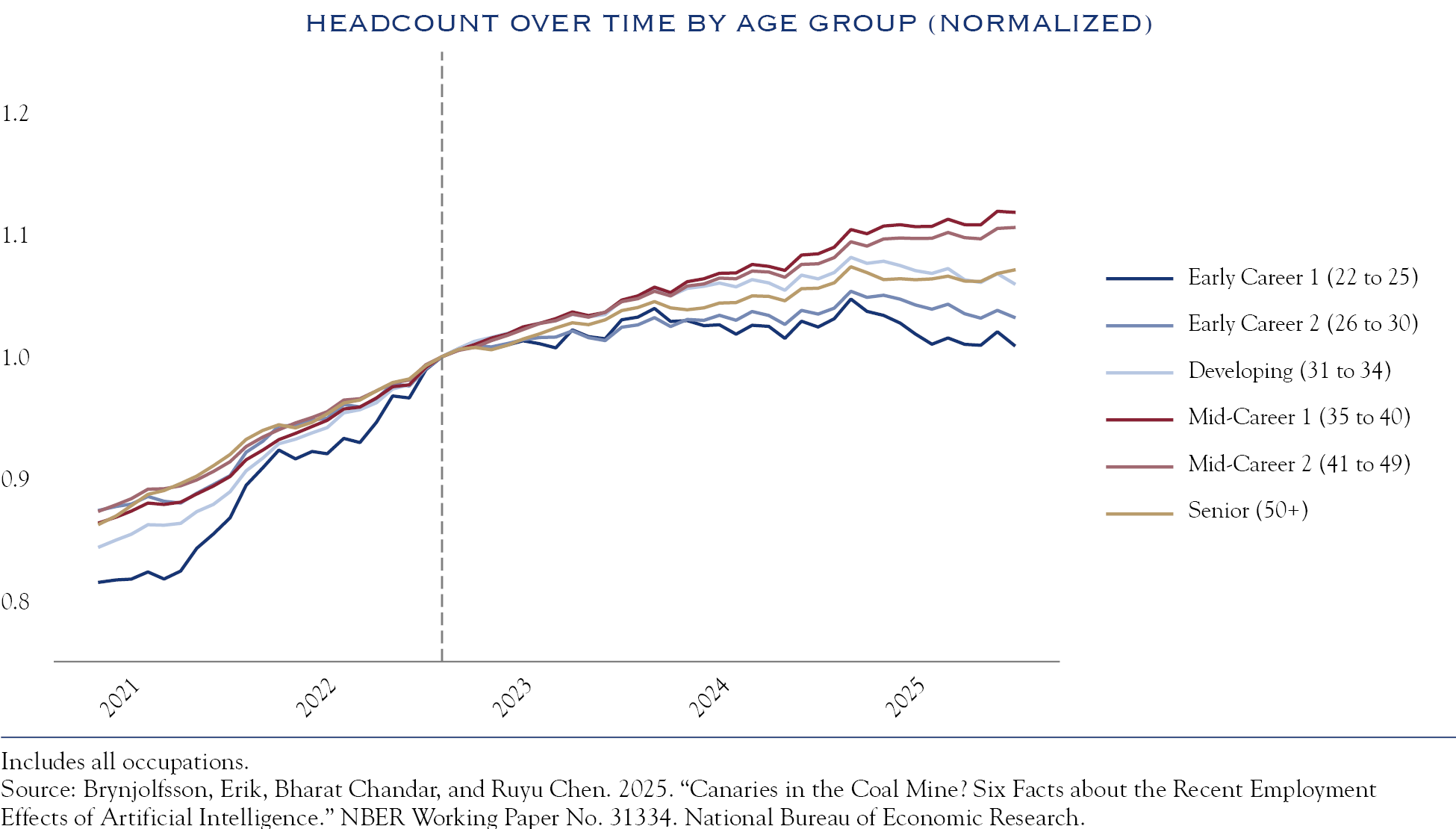

Most recently, Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen assessed whether generative AI is already having a measurable impact on employment and, if so, which workers are the first to be affected by generative AI.3 Using data from ADP, the largest payroll software provider in the United States, the paper presents six facts that characterize measurable shifts in the exposed occupations:

1) A significant and disproportionate employment decline has been observed among early-career workers (aged 22–25) in occupations most exposed to generative AI.

Employment for young workers in highly exposed roles (such as software development and customer service) fell by approximately 13% relative to the less-exposed occupations following the widespread adoption of generative AI after late 2022. In contrast, employment for older workers within the same occupations remained stable and/or continued to grow. The divergence implies that workers who are earlier in their careers are more vulnerable to task displacement from AI. Generative AI may be reshaping labor demand at the bottom of career ladders rather than uniformly across all age groups

2) While overall employment continues to grow, there is a notable stagnation in employment growth for early-career workers.

The stagnation is most concentrated in occupations exposed to AI. From late 2022 through mid-2025, workers aged 22–25 in highly exposed jobs experienced employment declines, while older workers in the same occupations saw continued growth. In the less-exposed occupations, young and older workers experienced similar employment trends. Aggregate labor market indicators can obscure important distributional effects of technological change, particularly for those younger entrants in the labor market.

3) Employment effects of generative AI depend critically on whether AI use substitutes for or complements human labor.

Using task-level data on observed queries to the large language model Claude, automated AI applications that replace human tasks can be empirically distinguished from augmentative applications that enhance worker productivity. The results indicate that entry-level employment declines are concentrated in occupations where AI primarily automates work, while occupations characterized by augmentative AI use experience stable or growing employment in all age categories.

4) Observed employment declines among young workers in AI-exposed occupations are not driven by firm or industry-level shocks.

Using an event study regression with firm time fixed effects, they control for aggregate shocks such as interest rate changes or sectoral downturns that affect all workers within a firm regardless of their exposure to AI. Even after accounting for these factors, workers aged 22–25 in the most AI-exposed occupations experience a statistically significant decline in employment relative to those in the least AI-exposed occupations, while the effects for older workers are smaller and insignificant.

5) Labor market adjustments are shown primarily through employment rather than wages.

Annual salary trends reveal little variation by age or exposure level, indicating short-run wage stickiness, where firms adjust to AI-driven changes in labor demand by reducing hiring or employment rather than cutting wages.

6) The findings are robust across a wide range of alternative sample constructions and are not driven by a narrow subset of occupations.

The results persist after accounting for remote work, outsourcing risks, and hold across both high- and low-college-share occupations. Importantly, measures of AI exposure did not meaningfully predict employment outcomes for young workers prior to the widespread adoption of large language models, with the observed effects emerging most sharply beginning in late 2022.

What The Evidence Suggests

Taken together, these findings help clarify a more measured and empirically grounded view of AI and its labor market effects. Rather than supporting narratives of rapid, economy-wide job destruction, the literature suggests that AI integration is a gradual, uneven process that reshapes the composition of work over time. Frey and Osborne provided the early conceptual framework, emphasizing that automation operates through task substitution and complementarity, and unfolds probabilistically over long horizons rather than through the immediate elimination of “at-risk” occupations. Brynjolfsson, Rock, and Syverson further explore why the economic effects of such technologies emerge slowly, highlighting the central role of intangible investments and organizational transformation that delays observable productivity gains (the J-Curve). Finally, more recent evidence from Brynjolfsson, Chandar, and Chen shows that the theories are now beginning to materialize in the labor market, with disruption concentrated among early-career workers and in occupations where AI substitutes for, rather than augments, human labor.

Together, these studies support our view that AI-driven technological changes are disruptive in transition, but structural in outcome, altering job tasks, careers, and skillset requirements rather than eliminating workers altogether. In this sense, AI appears less as a force that reduces the total number of jobs and more as one that changes which jobs exist and how labor is organized, consistent with historical patterns observed during prior technology transitions.

1 Frey, Carl Benedikt, and Michael A. Osborne. 2017. “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?”

2 Brynjolfsson, Erik, Daniel Rock, and Chad Syverson. 2021. “The Productivity J-Curve: How Intangibles Complement General Purpose Technologies.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics vol. 13, no. 1, January 2021(pp. 333–72)

3 Brynjolfsson, Erik, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen. 2025. “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence.” NBER Working Paper No. 31334. National Bureau of Economic Research.

This communication contains the personal opinions, as of the date set forth herein, about the securities, investments and/or economic subjects discussed by Mr. Viscichini. No part of Mr. Viscichini’s compensation was, is or will be related to any specific views contained in these materials. This communication is intended for information purposes only and does not recommend or solicit the purchase or sale of specific securities or investment services. Readers should not infer or assume that any securities, sectors or markets described were or will be profitable or are appropriate to meet the objectives, situation or needs of a particular individual or family, as the implementation of any financial strategy should only be made after consultation with your attorney, tax advisor and investment advisor. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. © Silvercrest Asset Management Group LLC