“Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.”

– Winston Churchill

Feel the Bern! Make America Great Again! Never Trump! The passions unleashed by this year’s rambunctious race for the U.S. presidency are hard to ignore, and make the outcome hard to predict. For investors, the tough question is: does it matter? Is all the campaign rhetoric and electoral drama so much sound and fury, signifying nothing, as far as markets are concerned? Or do they signify an important shift in American politics, with implications we should pay attention to?

Setting aside our personal convictions is one of the hardest parts of seeing politics as markets see them. Regardless of who should win, or will win, we do see important implications emerging from this contest, in the long run. In the short run, investors are better off not getting too wrapped up in—or scared away by—the noise.

The Noise of Democracy

Analysts have, for years, attempted to draw a predictable connection between the U.S. election cycle and stock market performance. Whatever links they claimed to find were dubious, little more credible than the supposed correlation between share prices and which baseball league won the World Series. Since 1928, the S&P 500 index (excluding dividends) rose an average of +7.0% in presidential election years, compared to +7.4% for all years. Small cap stocks rose +10.9% on average, versus +11.2% for all years. There were four elections where the S&P 500 fell more than 10%, and three where it rose more than 20%. The variations that do exist can be much better explained by prevailing economic conditions at the time, or preceding stock market trends, than by the elections themselves.

Some analysts posit that the stock market, disliking uncertainty, performs more poorly in election years (like this one) when there is no sitting incumbent running for reelection. It’s true that, when these years are tallied, S&P 500 gains average just +2.6%, well below par. But the sample size is so small (7 out of the past 22 elections) and the variation so large (from a +38% gain in 1928 to a −39% loss in 2008) that the predictive power of this observation is not particularly helpful. Exclude these two outliers, and average S&P 500 gains in years when Democrats won the White House (+7.1%) vary little from when Republicans won (+8.5%).

American presidential elections are momentous events, but normally not disruptive ones. Even presidents widely seen as transformative, like Franklin Roosevelt or Ronald Reagan, must contend with two other branches of government, and end up embracing much of what they inherited, either by design or default. Perhaps markets appreciate, implicitly, the realization President Truman voiced in a moment of profound frustration: “All the president is, is a glorified public relations man who spends his time flattering, kissing, and kicking people to get them to do what they are supposed to do anyway.” Call it continuity, call it inertia—in any case, electing a new president does not change everything.

Or does it? This year, at least two candidates—Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump—have ridden a wave of popular discontent by saying things you might think would get the market’s attention. Sanders, long the sole self-described “socialist” member of Congress, wants a single-payer government health care system (Medicare for All) as well as free college tuition funded by a tax on financial transactions, and has flirted with the idea of reinstating the World War II-era 90% marginal tax rate on high income earners. Trump proposes to round up and deport an estimated 11 million illegal immigrants en masse, block remittances to Mexico until it agrees to pay for building a border wall, and impose a 45% tariff on imports from China. He also says NATO is “obsolete” and threatens to withdraw from Europe as well from defense arrangements with Japan and South Korea, unless those countries pay more for U.S. protection.

Both men’s proposals—and rebel personas—have tapped into a deep wellspring of voter support. One key difference is that while Sanders’ mainly domestic initiatives would need to pass through (a currently Republican) Congress, many of Trump’s ideas could be implemented on his own authority, as president. Perhaps that’s why the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) recently ranked the possibility of Trump’s election as #6 on its list of Top 10 Geopolitical Risks for 2016. Even if, as many suspect, Trump’s bolder pronouncements are merely opening bargaining gambits, and not hard-and-fast commitments, they represent a significant break from the past. Which is the point: whatever you think about Sanders’ or Trump’s positions, love them or hate them, these are big changes they’re talking about that, if enacted, would certainly shake up anyone’s investment outlook.

So why are markets shrugging them off? Because most people don’t think they’re going to happen. Prediction markets currently give Hillary Clinton a 91% chance of winning the Democratic nomination. While they give Trump a 56% chance of winning the Republican nomination, they give him only a 15% chance of winning the presidency. In other words, they expect Hillary to defeat him handily—a view supported by the latest head-to-head polls. Since Clinton is perceived, for better or worse, as a status quo candidate, markets have little reason to revise their existing outlook.

The problem, of course, is that prediction markets have been consistently wrong throughout this election cycle. Before his fifth-place finish in New Hampshire on February 9, odds had Marco Rubio winning the GOP nomination; barely a month later, he was out of the race. Trump’s own chances of winning the nomination fell nearly 25 points (from a high of 80%) in the past two weeks, after a series of gaffes and missteps. The most likely outcome now is a contested Republican convention in July, where anything could happen. Meanwhile, a federal indictment of Hillary Clinton over her email scandal—unlikely, but certainly possible—would throw everything up for grabs. Even if today’s prediction markets prove right about the ultimate outcome, and about discounting the risks of a major policy shift, there is plenty of room for surprises between now and November that could contribute to the volatility that markets are already experiencing this year.

Feeling The Backlash

“I love the noise of democracy,” said President James Buchanan, who preceded Lincoln and is blamed by many historians with letting the country drift towards civil war. Amid all the noise he so enjoyed, there was a signal he missed: the nation was coming apart. So let us avoid his mistake, and shift our attention to the longer-term implications of the startling election we are witnessing: namely, the challenge to the existing U.S. political framework posed by a rising backlash against globalization.

Political parties are coalitions. Unlike in the proportional representation systems common in Europe, where multiple parties try to form majority coalitions after they are elected, the winner-take-all system in the U.S. tends to reward participants for cobbling together potentially dominant coalitions before voting takes place. Far from being homogenous organizations, the Democratic and Republican parties are ongoing attempts to reconcile disparate and evolving interests, ideologies, and demographics in the common pursuit of influence and power. If that sounds like a big headache, it is.

The modern Democratic coalition was forged in the fires of Roosevelt’s New Deal and the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. The modern Republican coalition is a product of the Conservative Movement crystalized, in the 1980s, by Ronald Reagan. Though they disagree and fight over many important issues, both coalitions share a common “dominant” gene that prevails over other, recessive traits in their make-up and has served as a cornerstone for globalization: a basic belief in the free flow of goods, capital, and ideas, and in a proactive U.S. role in the world to implement that vision.

Perhaps no moment symbolizes this bipartisan consensus more tellingly—for its advocates and detractors alike—than enactment of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1995: negotiated by a Republican president (Bush Sr.) and passed by his Democratic successor (Clinton) relying on votes from Republicans in Congress, over minority opposition in both parties. The third-party, populist bid by Ross Perot to derail the agreement proved quixotic at the time. Today it makes him look like John the Baptist, preparing the way for a greater revolt to come.

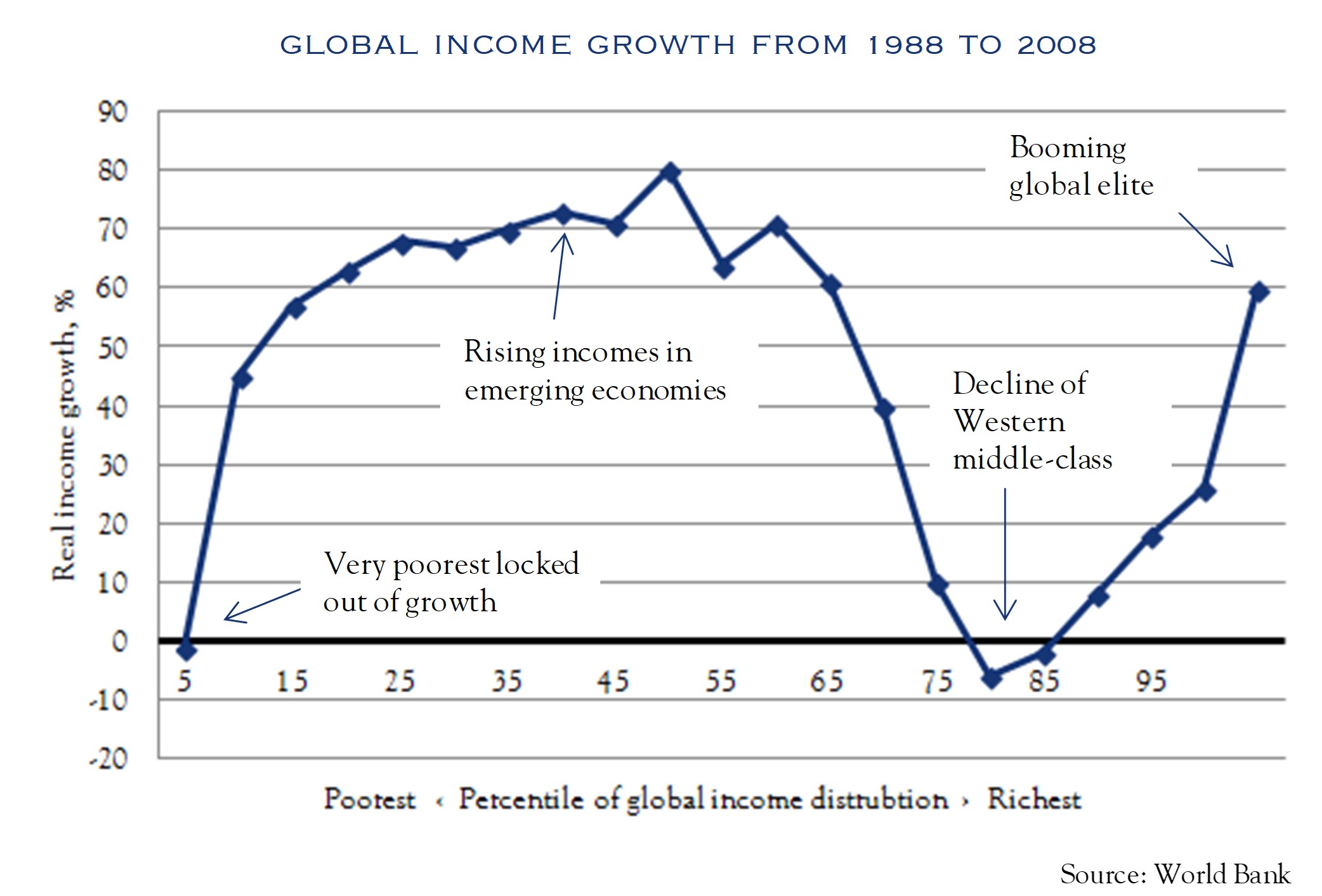

Over a year ago, in our 3Q14 letter, we highlighted the chart below as a key to understanding what has been taking place in the global economy. It shows a remarkable surge in incomes in emerging economies, connecting with opportunities created by trade and cross-border investment, along with the rewards for those now able to leverage their highly-demanded skills on a global scale. It also shows the stagnation or decline of those without skills to compete, or facing an onslaught of new competition. The first backlash to be felt was terrorism, from extreme and angry ideologies that festered among those left out of the global economy. Now we are starting to see a second backlash, from a frustrated middle class in the developed world (including the U.S.) that blames globalization—in the form of trade, outsourcing, and immigration—for benefiting others at their expense.

The result, this election season, has been a breakdown of the two main political parties into, in effect, four rival camps: Nationalists (Trump), Conservatives (Cruz, Kasich, and “The GOP Establishment”), Liberals (Clinton), and Socialists (Sanders). The Nationalists and the Socialists define themselves in opposition to globalization and the elites (read: Liberals and Conservatives) who they see as having betrayed the middle class. As products of the backlash, they actually have more in common with each other than with their ostensible compatriots on the Right or the Left—which helps account for the otherwise inexplicable phenomenon of Sanders voters who name Trump as their second choice, and vice versa. (Nor is this backlash confined to U.S. politics: we see it clearly reflected in Europe in the rise of nationalist parties like UKIP, and anti-capitalist ones like Greece’s Syriza and Spain’s Podemos.)

But just as nature abhors a vacuum, the winner-take-all U.S. electoral system abhors fragmented minority parties. When divisions do occur, party coalitions reshuffle, in search of a winning majority. Sometimes the breach heals on its own, at least for a time, as when Dixiecrats who revolted in 1948 rejoined the Democratic coalition for another two decades. Other times, voters who split from one party simply migrate to the other: many of the “Bull Moose” Republicans who broke away with Teddy Roosevelt 1912 ended up as New Deal Democrats, just as Southern Democrats who voted for George Wallace in 1968 joined Nixon’s “Silent Majority” by 1972. In some cases, however, the ruptures run too deep and there is no logical place to go, as when both parties, Whigs and Democrats, fractured over slavery and immigration in the 1850s. It’s easy to forget that Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860 with only 40% of the vote, with the rest divided between three other candidates. The Whig Party disappeared entirely, replaced by a new (Republican) coalition that had to win on the battlefield, as well as at the ballot box.

This year, Republicans appear to be much more deeply divided than Democrats. According to a recent Pew Research poll, 64% of Democrats expect their party to unite behind Hillary Clinton if she is the nominee, similar to the number who said the party would unite behind Clinton or Obama in 2008. Only 38% of Republicans (including a majority of Trump supporters) expect the GOP to unite behind Trump if he is the nominee. A majority of Cruz and Kasich supporters say Trump would make a “poor” or “terrible” president, giving rise to last-ditch talk of running an “alternative” candidate against both Trump and Clinton in the general election—presuming a willing champion could be found. Meanwhile, Trump mutters darkly about “riots” breaking out if he is denied the nomination. Such deep divisions at the top of the ticket have some Republican strategists worried the party could lose its majority hold over the Senate, and even the House. If a swing in control of Congress does take place, it would undoubtedly have significant ramifications for government policy, and with it, our economic outlook and investment strategy.

Over the longer haul, both political parties will struggle to redefine themselves along lines they hope can recapture a majority of voters. On immigration, the parties have adopted opposite tacks, with Democrats betting that a migrant-friendly stance will win them enough votes from a rapidly growing Latino population to outweigh any backlash. A deep skepticism of immigration among Republican voters (53% tell Pew they think immigrants have an overall negative effect on the country, compared to just 24% of Democrats and 37% of Independents) has pushed the GOP to take the opposite side of that bet. The impasse has made it impossible to work together on what should be far less controversial measures to attract and retain high-skill immigrants, who nearly everyone agrees are needed to create jobs and grow the economy.

Perhaps the greatest shift we have witnessed is on trade. One of the most remarkable developments in this campaign is that all four of the leading candidates (except for Kasich) have come out against the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), in increasingly trenchant terms as the campaign has progressed. Although a majority of Americans (51%) polled by Pew still say free trade agreements have been a “good thing” for the U.S., that support has wavered in recent years, and 53% of Republican voters now say they have been a “bad thing.” The intensity of opposition (67%) among Trump supporters, along with widespread Republican distrust of any Obama initiative, has undoubtedly influenced Cruz, but Sanders’ adamant opposition has clearly put Clinton on the defensive, despite 56% of Democrats voicing a positive view of past free trade deals. TPP is the economic centerpiece of U.S. policy in Asia, and the template for a similar deal (TTIP) with Europe. A number of countries, such as Japan and Indonesia, are looking to TPP as a vehicle for critical domestic reforms to revive growth. For the U.S. to walk away from TPP—as each of the leading candidates for president now says they will do—would be a serious step indeed.

On The (Fragile) Rebound

“Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all others”—which is exactly why we should keep these concerns, and uncertainties, in perspective. The market, with its eyes firmly fixed on latest economic data, isn’t losing its cool, and neither should we. In March, in fact, global equity markets saw a sharp rebound as it become evident that two things we’ve been saying were right all along: that (1) a slowing China and cheap oil prices were not pushing the U.S. into a recession, as many feared, and (2) amid such concerns, the Fed will show patience in raising rates. After a dismal January and a stable February, the S&P 500 bounced back +6.6% in March, for a total return of +1.4% since the year began.

The Fed’s decision not to raise rates in March, as well as scale back its schedule of anticipated rate hikes this year, from four to two, provided immediate relief in the form of a weaker U.S. Dollar. The Dollar fell −3.6% in March, on a trade-weighted basis, down −2.9% on the year

(−4.9% against other major currencies). The move should boost the value of U.S. corporate earnings abroad, improve their domestic pricing power, and revive exports—all of which suffered from a strong Dollar last year. It should also relieve some of the pressure on China to let its currency slide relative to the Dollar, giving the global economy a bit of breathing space.

Strong jobs growth in March, which saw a +215,000 net gain to non-farm payrolls, reflects continuing momentum in the economy, and should support that momentum by fueling healthy consumption growth. The unemployment rate ticked up slightly to 5.0%, but only due to a welcome rebound in the labor participation rate. Hourly wages rose by +0.3%, up +2.3% from a year ago, which represents real gains over inflation, especially given cheaper fuel prices. Retail sales have been wobbly so far this year, but excluding gasoline, are still up +4.8% from last year. Automobile sales stumbled in March, after a red-hot streak, amid worries about rising default rates on car loans, but overall, measures of consumer confidence remain strong.

The housing market, which saw a solid rebound last year, has cooled a bit in recent months. Home prices are showing continued strength, however, up +5.7% from a year ago, helping support household balance sheets. Residential and non-residential construction spending are both up over +10% from a year ago.

The shakeout in raw materials continues to weigh on industrial production (down −1.6% from a year ago), and capital goods orders fell −2.5% in February, pointing to ongoing weakness in business investment. But the struggling manufacturing sector is seeing some glimmers of hope. Output was up +0.1% in February, up +1.1% from a year before. The ISM Manufacturing Index actually returned to expansion territory (51.8) in March, following a five-month string of negative readings, led by a surge in new orders, including export orders, which hit their strongest level since December 2014. The ISM Non-Manufacturing Index, which covers a much larger portion of the U.S. economy, continues to register the solid expansion (54.5) it did throughout all last year.

A couple of concerns loom over this relatively positive picture. First, inventory-to-sales ratios, at the factory, wholesale, and retail level, are elevated relative to trend, and have been rising steadily, making businesses reluctant to expand production or place new orders. Second, while stockpiles of refined fuel have declined, U.S. crude oil inventories continue to rise to record new heights. Until this stockpiling begins to level off, we are reluctant to place too much confidence in the recent recovery in oil prices.

While we welcome the recent rebound in share prices, we remain conscious that the S&P 500 remains richly valued at 19.5x our earnings projection for 2016. Recognizing a number of headwinds companies faced in 2015, our earnings projections were consistently more cautious than consensus, and rightly so. This year, earnings performance remains highly uneven, and we believe that a modest recovery to $105.50 is more realistic than the consensus projection that earnings will rebound +18%, largely in the final quarter, driven by a powerful turnaround in energy and materials. We also think that last month’s +13% surge in emerging market shares, driven by renewed optimism in the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, and China), is built on a number of assumptions that may prove equally fragile. In other words, the sky is not the limit. Nor are we gazing over the edge of any abyss. The far more mundane reality is that we are in an economy that is growing, albeit sluggishly, and has weaknesses and vulnerabilities of which we are well aware—not least of which, an American political scene that’s just full of surprises.

This communication contains the personal opinions, as of the date set forth herein, about the securities, investments and/or economic subjects discussed by Mr. Chovanec. No part of Mr. Chovanec’s compensation was, is or will be related to any specific views contained in these materials. This communication is intended for information purposes only and does not recommend or solicit the purchase or sale of specific securities or investment services. Readers should not infer or assume that any securities, sectors or markets described were or will be profitable or are appropriate to meet the objectives, situation or needs of a particular individual or family, as the implementation of any financial strategy should only be made after consultation with your attorney, tax advisor and investment advisor. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. © Silvercrest Asset Management Group LLC