In his latest testimony to Congress, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell had good words to say about the U.S. economy. “We view current economic conditions as healthy and the economic outlook as favorable,” he observed, but added that “over the past few months we have seen some crosscurrents and conflicting signals.” Chief among them, he noted that “Growth has slowed in some major foreign economies, particularly China and Europe.”

Weakness overseas poses a possible stumbling block to U.S. growth and corporate earnings, but it also reduces pressure on the Fed to hike interest rates, a let-up that could help prolong the current business and market cycle. We think it’s premature to be calling a final peak to the market and running for cover. Those who gave into that reflex late last year missed a +13.1% rebound to the S&P 500, its strongest 3-month opening since 1998. The uncertainty hanging over markets is real, but it’s pushing people to pay far too much to avoid risk, and leaving a lot of returns behind for a disciplined, longer-term focused investor to collect.

A Shift in the Wind

Fears of a slowing China played a leading part in prompting the last three market corrections, and are back once again. Officially, China’s GDP growth slowed to +6.6% in 2018, its slowest rate pace in nearly 30 years, and a Reuters poll of economist predicts it could slow to +6.3% this year. But Michael Pettis of Peking University, one of a growing number of skeptics of the government’s official economic data, says China’s true growth rate is probably “less than half of that.” While China’s independent Caixin Manufacturing PMI saw a modest improvement in March, the prior three months were spent in contraction, a telling sign for an economy billed as the “workshop of the world.”

For anyone who hasn’t kept a close eye on China over the past many years, there’s a tendency to blame its slowdown on trade tensions with the U.S.—and assume that a much-rumored trade deal between Presidents Trump and Xi would set things right again. That line of thinking is precisely why the Shanghai Composite stock index, which dropped −25% last year, bounced back +24% in the past three months.

The real reasons for China’s slowdown go much deeper. In fact, it was in reaction to an earlier export shock from the U.S.—caused by falling demand in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis—that China became addicted to rampant over-investment, fueled by runaway credit expansion, as an alternative means of driving growth. This building binge has generated a growing burden of unacknowledged bad debt, which has been weighing down the Chinese economy. This became evident in 2015 and 2016 when the Caixin Manufacturing PMI went into contraction, for 16 straight months, as did non-state investment. Rather than implementing promised reforms, Beijing responded by reopening the credit spigots, in anticipation of a crucial Communist Party Congress in late 2017, where Xi succeeded in abolishing term limits on his rule. China’s economy got a temporary boost, convincing many investors that its troubles had passed; in fact, they had only grown that much bigger. China now finds itself waking up to the hangover, though it keeps trying to put one off by pouring another drink.

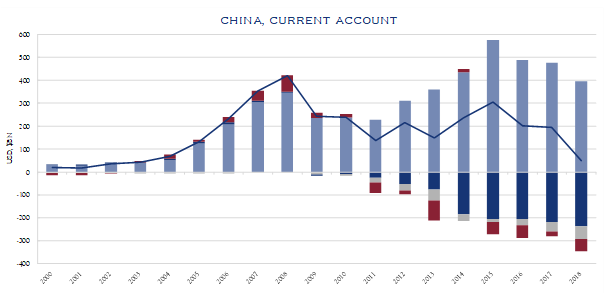

The assumption is that when the world’s second-largest economy slows, that must be a bad thing for everyone else. That’s not necessarily so. What matters to the rest of the world, in terms of driving growth, is not how much China produces (measured by slowing GDP growth) but how much it consumes. For years, China has produced more than it consumed by running chronic trade surpluses. That imbalance, and the excessive investment that has gone into it, is unsustainable; but the good news, for everyone, is that as that output gets reined in, China can afford to cushion the blow by consuming more than it produces. That’s precisely what appears to be happening. As the chart below shows, starting in 2015, China’s current account surplus has steadily decreased, to just 0.4% of GDP, and is widely expected to go into deficit this year. The shift is partly driven by China buying more imports (its latest surplus in goods was the lowest in five years), but also by a huge rise in Chinese tourists traveling and spending money abroad (a net outflow of $237 billion in 2018).

![]()

Source: SAFE (State Administration of Foreign Exchange)

China running trade deficits, as its output growth slows and even stumbles, should help sustain growth in the U.S. and many other countries. But the process of rebalancing is neither smooth nor easy. Sectors and countries that have thrived on China’s existing, lop-sided patterns of growth are taking a hit. Australia’s economy, propelled by China’s seemingly insatiable demand for iron ore, often recycled as property purchases, has slowed noticeably. South Korea’s exports, many of which feed into China’s industrial supply chains, fell for the third straight month in February, down −11.1% from a year ago. Slowing growth in Chinese energy demand helped trigger a steep global drop in oil prices, starting in 2015, which have yet to fully recover, putting great pressure on marginal producers like Nigeria and Venezuela. Even Chinese spending on some consumer goods—such as automobiles, whose sales fell −2.8% last year, their first annual decline in China since 1990—may face short-term setbacks as Chinese households grapple with new uncertainties. Meanwhile, countries looking to China’s much-heralded overseas investment initiatives, like One Belt One Road, to ramp up their own investment-led growth may find the funds drying up, as China diverts its savings into consumption instead.

U.S. trade sanctions may have focused market attention on China’s renewed slowdown, and even contributed to it. But China’s economy would be slowing anyway, with or without a trade war, and a deal to resolve tensions won’t change that. To the contrary, a deal that’s actually meaningful would tie China’s hands from propping up growth the easiest way it knows how, by piling on more debt and over-capacity. What a deal would avoid is an all-out trade war, which might tempt China to retaliate by devaluing its currency in an effort to shore up exports—a move that could shift real damage onto the U.S. economy. From April to November last year, as trade tensions escalated, China let the yuan slide −10% against the dollar, helping to offset new tariffs. An agreement on trade that removes at least one rationale for China to go down this path would be welcome news, even if it offers no quick fixes for China’s slowdown.

Stuck in Low Gear

China may weigh on investors’ minds, but it can’t match Europe in drama. Italy went into recession in the second half of 2018, while Germany teetered right on the edge. In late March, a raft of strikingly bad PMI numbers, which appeared to show Europe slowing further, pulled German 10-year bond yields back into negative territory, and caused the U.S. yield curve to partially invert. And then there’s the Brexit saga.

Henry Kissinger is said to have joked that he knew how to reach the leaders of Russia or China, but “Where do I call if I want to speak to Europe?” Conflicting agendas and fragmented decision-making can often make the European Union—which has an economy 40% larger than China’s, and nearly four times bigger than Japan’s—look less like a Great Power and more like the Greatest Show on Earth. As with any good circus, this one has three rings to keep an eye on right now: Britain, Italy, and Germany.

Britain was scheduled to leave the E.U. on March 29 but, as we anticipated, that didn’t happen. While a slim majority may have voted in favor of Brexit three years ago, Parliament appears unable to either accept the terms negotiated with the E.U., take the plunge without a deal, or reconsider the decision to leave. The “leave date” has been postponed to April 12, or possibly a bit later, but it’s unclear what will change by then, and further extensions are complicated by the need for Britain to participate—if it hasn’t left yet—in upcoming European parliamentary elections. Politically, at least, it’s been a train wreck, and the possibility of a “no deal” Brexit can no longer be discounted. The growing uncertainty has caused businesses to cut back on investment, slowing U.K. GDP growth to an annual rate of just +0.9% in Q4. Yet British consumer spending has remained surprisingly resilient, bolstering the assertions of those like former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King who say the U.K. could shrug off even a “crash” Brexit without too much damage. We aren’t quite as sanguine and see the economic impact of a “no deal” Brexit—which London and Brussels have done little to prepare for—more along the lines of a natural disaster: creating potentially costly short-term disruptions, which people eventually figure out ways to recover from. But it’s hardly the kind of shock Britain or the rest of Europe could use right now.

Italy is already in recession, and there’s plenty of blame to go around. Critics blame the country’s populist government, led by Giuseppe Conti, for undercutting business and consumer confidence by clashing with the E.U. over its budget, and for blocking key infrastructure projects. The populists, in turn, blame Germany’s slowdown on top of years of E.U.-imposed austerity. In any case, we’re a long way from the heady days in 2014 when markets greeted the rise of energetic reformist Matteo Renzi as evidence that Italy could get its act together. Italy’s economy is −5% smaller than it was in early 2008. But the real risk it poses to everyone else is contagion. Worries periodically crop up about the health of Italy’s banks, and the spread on its 10-year sovereign bonds (over German bunds) is up more than 100 basis points since the populists took power a year ago, the highest level since 2013. With the European Central Bank (ECB) halting its bond-buying program in December, Italy remains part of a “soft underbelly” that could serve as a conduit to introducing fear of financial instability elsewhere into Europe. Spain, which unlike Italy grew at a healthy annual rate of +2.8% in Q4, could pose a similar risk: its banks have lent heavily to Turkey, which is facing a deepening debt and currency crisis.

Throughout Europe’s recent travails, Germany has been the rock. Its strong export sector and high savings rate has made it the financial guarantor for the rest of the Eurozone. But after shrinking at an annualized rate of −0.8% in Q3, the German economy grew by just +0.1% in Q4. Some blame confusion over new emission standards for setting back car sales, and low water levels on the Rhine for holding up shipments, and it’s true that German retail sales appear to have bounced back from a dismal December. In March, however, Germany’s Manufacturing PMI fell to 44.7, its third straight month in contraction and its lowest level in over six years. The downturn was driven by a big slump in export orders, giving credence to the widespread impression that China’s slowdown is taking a toll on German machinery and vehicle exports—a problem that could prove more persistent. The country’s Council of Economic Experts recently cut its GDP growth forecast for 2019 to +0.8%, down from +1.8%. The slowdown comes at a sensitive political time as Chancellor Angela Merkel prepares to step down the year after next, amid popular backlash against her open-arms refugee policy. Merkel, who has led Germany since 2005, has really been the key decision maker in crisis after crisis, the lynchpin holding the E.U. together at critical moments; no one knows who, if anyone, will step in to fill her shoes.

Europe’s difficulties could have a much bigger drag on the U.S. economy than China’s. Europe accounts for 55% of all overseas income earned by U.S. multinational corporations. Their affiliates in Europe made $284 billion in 2018, up +7% from the year before, compared to $13 billion in China, which was down −1%. In many ways, it’s a success story: Europe enjoys immense advantages in infrastructure, human capital, and cultural “soft power”. But it’s stuck in low gear. After years of “recovery”, youth unemployment in the Eurozone stands at 17%, and as high as 33% in Italy and Spain. France’s economy grew +1.5% in 2018, its second-best rate in seven years, but the protests and riots filling the streets—and stalling the reform agenda of President Emmanuel Macron—are evidence that’s not good enough. A region that should be generating opportunity is instead generating mounting frustration. The prospect of a new cyclical downturn, adding to this tension and paralysis, is daunting. The ECB has already pressed as hard on the monetary gas pedal as it knows how. It’s going to take more than that to turn things around, and it’s hard to see where the “political will” will come from.

Mixed Signals

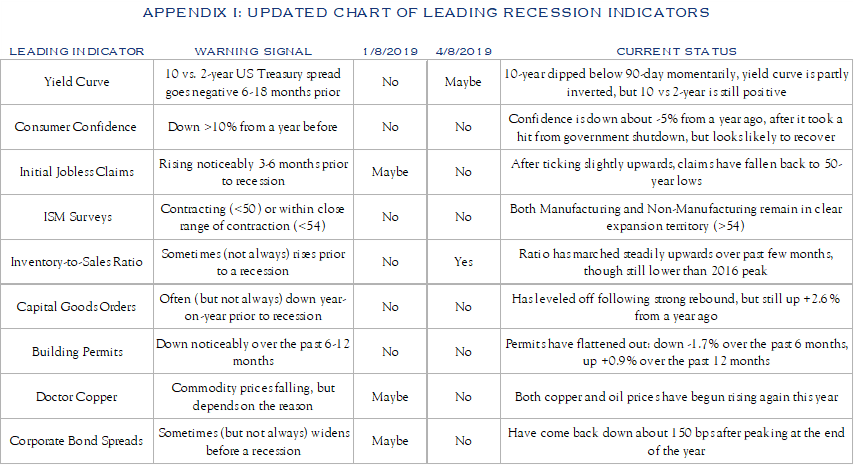

Over the past half year, the U.S. economy has also slowed. Coming down from a strong summer, where Q2 growth reached +4.2%, GDP growth cooled to +2.2% in Q4. The Atlanta Fed currently projects Q1 growth will come in at +2.3%, the New York Fed at +1.4%. Consumer confidence took a hit from the federal government shutdown in January and has yet to fully recover, though it remains relatively high. Retail sales fell −0.2% in February, up an unimpressive +2.2% from a year ago, pulled down by furniture, appliance, and electronics sales hurt by a slumping housing market. The inventory-to-sales ratio, which we highlighted in last quarter’s note as a potential red flag, has been steadily rising. Durable goods orders, aside from volatile aircraft purchases, have plateaued since last spring. The last two years’ sizeable bounce in capital goods orders, following a slump in 2016, appears to be over.

Yet other data suggests that U.S. growth momentum remains quite resilient. The ISM Manufacturing Index rose +1.1 points in March to 55.3, its 31st straight month of expansion, as surveyed companies voiced optimism and reported full order books. “Business remains very strong amid rumors of a slowdown,” went one typical response. The broader Non-Manufacturing Index eased −3.6 points in March to 56.1, which is still solid expansion territory. The U.S. economy continues adding jobs at a healthy pace: +196,000 in March. Initial jobless claims (which had ticked up) have dropped back to 50-year lows, while wage growth (up +3.2% from a year ago) has steadily gained momentum. As a result, personal income is up a solid +4.3% from a year ago, which should help bolster consumer spending. Even the housing market, which dragged on GDP growth for four straight quarters last year, is showing signs of life. New and existing home sales, along with residential construction spending, all seem to be finally pulling their noses up, though new housing starts remain skittish.

Nevertheless, it’s clear that, after getting a double-digit boost through most of last year from a big tax cut, U.S. corporate profits have entered a soft patch. After-tax profits across the economy as a whole declined −1.7% from Q3 to Q4, though they were still up +11.1% from a year ago. The S&P 500, which derives nearly 40% of its earnings from abroad, saw a sharp and unexpected slowdown in quarterly operating earnings per share (EPS) in Q4, reining in growth to a more modest +3.5% from a year ago. If this quarter’s earnings rebound as expected, it will only put them up +0.8% from a year ago; in fact, all but two out of 11 sectors (health care and financials) are expected to be down over 12 months. In contrast to 2015, when the S&P 500 experienced an earnings recession driven almost entirely by the energy and materials sectors, this downturn is being felt across a much broader range of industries.

Much of this earnings downturn was already priced—one could argue over-priced—into the market in December’s big sell-off, which pulled the 12-month trailing P/E ratio for the S&P 500 down to an almost 6-year low of 16.5x operating earnings. With few signs of a U.S. recession imminent, that was overshooting, and the index bounced back +13.1% in Q1. If Q1 earnings come in as expected, that would put valuations back to 18.7x—a far cry from their peak (21.5x) at the start of 2018, but high enough that the market will likely want to see earnings back on an upwards path before advancing much higher.

One important piece of good news, for markets and the economy, is the Fed’s decision that it can afford to be patient in raising interest rates further. Part of what drove the stock market sell-off at the end of last year was concern that the Fed would stick to its plan of hiking rates 3–4 times in 2019, tipping a slowing U.S. economy into recession. In light of weakness overseas, and more mixed data in the U.S., the Fed now says it expects to hold rates steady this year, and raise them only once in 2020. One reason it can hold off is that inflation, rather than accelerating as many worried, has actually slowed. The Producer Price Index, often an early warning flag, peaked at +3.4% last summer and has fallen to +1.8%. The PCE price index, the Fed’s go-to inflation gauge, slowed to an annual rate of just +1.5% in Q4. Both are below the Fed’s target inflation rate of 2%. In fact, given where inflation is now, some—including the Trump White House—are even urging the Fed to proactively cut rates to shore up growth. With wages and oil prices rising, and the ISM surveys hinting at price pressure turning up again, we think talk of rate-cutting is premature, but for the moment the Fed has room to hold its fire.

Slowing growth overseas is a double-edged sword: while it threatens to undercut growth and profits in the U.S., it also keeps inflation and interest rates here in check. The less it costs to borrow, the easier it is for companies to make major investments and consumers to afford big purchases like homes and cars. Lower interest rates also make an equity stake in corporate earnings look more attractive and boosts share prices—as long as those earnings hold up. Of course, if weakness abroad translates into a U.S. recession, low interest rates won’t save the stock market. But unlike a few months ago, it no longer looks like a rate-hiking Fed will be the one to put an end to this cycle.

In my last monthly market view, for March, I noted that “Growing up in the Midwest, I was well familiar with the difference between a Tornado Watch and a Tornado Warning. A Watch meant that conditions were potentially right for a cyclone, so keep your eyes and ears open. A Warning meant that a funnel cloud had been actually sighted, so head down to your basement.” We remain in Watch mode, not Warning. Growth has slowed, and we are aware of a number of factors that might slow it further. But it is far from clear that they will prevail over the positive growth momentum that continues to drive the U.S. economy. Nor does every recession equate to the kind of global financial crisis that haunts investors’ nightmares.

Faced with uncertainty, the natural instinct is to shrink from risk and seek safety. Investors, nervous about the next recession, have once again pushed the equity risk premium up to 5.8%. They are willing to forego substantial claims on cash flow, until and probably after the cycle eventually ends, to insulate themselves from any downturn. Their peace of mind, however, is dearly bought. To the extent that a disciplined investor, with their eyes focused on the longer term, can afford to accept and ride out the market’s ups and downs, instead of paying to avoid them, they stand to reap this hefty “fear dividend” and come out ahead.

This communication contains the personal opinions, as of the date set forth herein, about the securities, investments and/or economic subjects discussed by Mr. Chovanec. No part of Mr. Chovanec’s compensation was, is or will be related to any specific views contained in these materials. This communication is intended for information purposes only and does not recommend or solicit the purchase or sale of specific securities or investment services. Readers should not infer or assume that any securities, sectors or markets described were or will be profitable or are appropriate to meet the objectives, situation or needs of a particular individual or family, as the implementation of any financial strategy should only be made after consultation with your attorney, tax advisor and investment advisor. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. © Silvercrest Asset Management Group LLC